House of God Meaning in Bible: Sacred Dwelling

In the Bible, the ‘House of God‘ evolves in meaning from early altars marking divine encounters (Genesis 12:7-8) to the Tabernacle of Moses, a mobile sanctuary representing God’s presence (Exodus 25:8). Solomon’s Temple, a magnificent permanent edifice, centralized worship in Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 3:1).

The Second Temple continued as the locus for sacrificial rites and spiritual observance (Ezra 6:15). With Jesus’ New Covenant, the concept shifted to the Church as a spiritual house embodying God’s presence among believers (Ephesians 2:19-22).

Understanding these transformations reveals profound theological insights into worship and community through Scripture.

House of God Meaning in the Bible – Understanding Sacred Spaces

| Concept | Meaning/Significance | Scripture Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bethel (House of God) | Refers to a physical place where God’s presence dwells | Genesis 28:19, 1 Kings 12:29 |

| Temple of Solomon | Symbolized God’s dwelling among His people, a holy sanctuary | 1 Kings 6:1-14, 2 Chronicles 7:16 |

| The Church | Represents the spiritual body of believers, the New Testament House of God | 1 Timothy 3:15, Ephesians 2:19-22 |

| Individual Believers | The body of believers is the temple of the Holy Spirit | 1 Corinthians 6:19, 2 Corinthians 6:16 |

| Heavenly House of God | Refers to the ultimate eternal dwelling place with God | Hebrews 12:22, John 14:2 |

Early Altars and Patriarchs

In the earliest chapters of the Bible, the construction of altars by patriarchs such as Noah, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob signifies pivotal moments of divine encounter and covenantal milestones.

Noah’s altar, post-flood (Genesis 8:20), marks a new covenant with God, symbolizing renewal and divine favor.

Abraham’s numerous altars (e.g., Genesis 12:7-8, 13:18) not only signify worship but also the reaffirmation of God’s promises.

Isaac’s altar at Beersheba (Genesis 26:25) represents God’s continued covenantal faithfulness.

Jacob’s altar at Bethel (Genesis 35:7) commemorates his transformative encounter with God.

These altars, consequently, serve as tangible manifestations of divine-human interaction and covenant, prefiguring the more structured worship spaces that follow in biblical history.

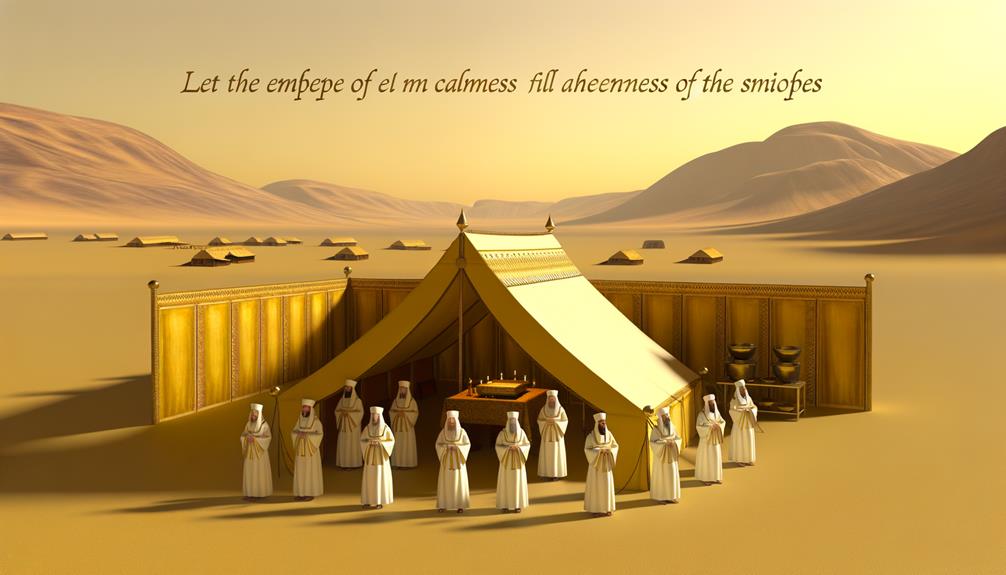

The Tabernacle of Moses

The Tabernacle of Moses, as described in Exodus 25-31, served as a divine dwelling place and a focal point for Israelite worship, embodying God’s presence among His people.

Its intricate design and structure, specified by God, symbolized the holiness and order of divine worship, encompassing the Outer Court, the Holy Place, and the Holy of Holies.

Understanding the tabernacle’s purpose and significance not only provides insight into ancient Israelite religious practice but also prefigures the ultimate revelation of God’s presence in the New Covenant.

Purpose and Significance

Moses’ Tabernacle, as detailed in the Book of Exodus, served as a divinely ordained meeting place between God and His people, symbolizing the presence and holiness of the Almighty among the Israelites. The purpose and significance of the Tabernacle can be understood through several key aspects:

- Divine Presence: It provided a tangible representation of God’s dwelling among His people (Exodus 25:8).

- Worship and Sacrifice: It was the central location for offerings and rituals as dictated by Mosaic Law (Leviticus 1-7).

- Covenantal Relationship: The Tabernacle reinforced the covenantal bond between God and Israel (Exodus 29:45-46).

- Spiritual Instruction: The structure and its services were rich in symbolism, teaching spiritual truths and foreshadowing Christ’s redemptive work (Hebrews 9:11-12).

Structure and Design

Crafted according to divine specifications, the Tabernacle’s intricate structure and design are meticulously detailed in Exodus 25-27, showcasing the profound theological and symbolic significance embedded within its construction.

The Tabernacle was divided into three main sections: the Outer Court, the Holy Place, and the Holy of Holies, each symbolizing different aspects of the divine-human relationship.

The use of gold, silver, and bronze, along with acacia wood and fine linens, not only served practical purposes but also highlighted the sanctity and purity required for worship.

The Ark of the Covenant, the Table of Showbread, and the Golden Lampstand each held deep religious symbolism, representing God’s covenant, provision, and light, respectively.

This intricate design underscores God’s desire for order and holiness.

Solomon’s Temple

Solomon’s Temple, often regarded as one of the most magnificent edifices in biblical history, serves as a profound symbol of divine presence and covenant. According to 1 Kings 6, its construction marked a pivotal moment in Israel’s religious and cultural life.

Theologically, Solomon’s Temple epitomizes:

- Divine Selection: The site was chosen by God (2 Chronicles 3:1).

- Covenantal Fulfillment: It fulfilled God’s promise to David (2 Samuel 7:13).

- Worship Centralization: It centralized worship in Jerusalem (Deuteronomy 12:5-14).

- Sacrificial System: It established the sacrificial system essential for atonement (Leviticus 16).

This sanctuary not only represented God’s dwelling among His people but also underscored Israel’s unique relationship with Yahweh.

The Second Temple

The Second Temple, built under the auspices of Zerubbabel and later expanded by Herod, stands as a witness to the resilience and continuity of Jewish worship and identity post-exile. This sacred edifice, initiated in 516 BCE as per Ezra 6:15, symbolizes the restoration of Israel’s covenantal relationship with Yahweh.

It was a center of sacrificial rites and religious observance, embodying the prophetic vision of Haggai and Zechariah. Herod the Great’s extensive renovations (John 2:20) transformed it into a monumental structure, further solidifying its religious and cultural significance.

The Second Temple’s existence underscores the unbroken thread of worship from Solomon’s Temple, despite the Babylonian destruction, reflecting the enduring faith and communal identity of the Jewish people.

Jesus and the New Covenant

In the New Scripture, Jesus is portrayed as the mediator of a New Covenant, fulfilling and transcending the Mosaic Law as prophesied in Jeremiah 31:31-34. This New Covenant signifies a profound shift in how humanity relates to God, emphasizing internal transformation over external observance.

Key elements include:

- Fulfillment of Prophecy: Jesus’ life and teachings fulfill the promises made in the Hebrew Scriptures.

- Sacrificial Atonement: His death serves as the ultimate sacrifice, replacing the need for continual offerings (Hebrews 9:15).

- Universal Access: The New Covenant extends God’s grace beyond Israel to all nations (Galatians 3:28).

- Inner Transformation: The Law is now written on believers’ hearts, signifying an internalized, spiritual relationship with God (Hebrews 8:10).

The Church as God’s House

Building upon the New Covenant established by Jesus, the Church emerges as the new ‘House of God,’ embodying a spiritual temple where believers collectively become the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit (Ephesians 2:19-22).

This ecclesiological paradigm shift signifies that the presence of God is not confined to a physical structure but is dynamically present within the community of believers.

Scriptural references such as 1 Corinthians 3:16-17 emphasize that the Church, as the body of Christ, is sacred and holy, a living temple where God resides.

Further, 1 Peter 2:5 describes believers as ‘living stones,’ contributing to the spiritual edifice.

Consequently, the Church as God’s House underscores a relational and communal dimension, pivotal to New Covenant theology. The Church, as God’s House, is not just a physical building but a living community of believers who are called to love, support, and encourage one another. This reflects the significance of unity in the Bible, as seen in passages such as Ephesians 4:3 which calls believers to “make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace. ” This unity within the Church is a testament to the transformative power of God’s love and grace, and is integral to fulfilling the New Covenant theology of bearing one another’s burdens and living in harmony with one another.

Conclusion

The evolution from early altars and patriarchs to the grandiosity of Solomon’s Temple, juxtaposed with the humble origins of Jesus’ new covenant, underscores a divine narrative of accessibility and sacredness.

The change from physical edifices to the Church as God’s house illustrates a shift from tangible to spiritual, from exclusive to inclusive.

This theological journey, grounded in scriptural references, highlights the ever-present and transforming nature of the divine dwelling among humanity. As believers reflect on their experiences, they come to understand the profound implications of God’s presence in their daily lives. This journey invites them to explore the meaning of work in the Bible, revealing how their labor is not merely a means to an end but a sacred vocation fostering connection with the divine. By embracing this perspective, individuals can find purpose and fulfillment in their contributions, recognizing that their efforts are intertwined with the greater tapestry of God’s plan.