Meaning of the Word Church in the Bible: Community

The word ‘Church’ in the Bible, derived from the Greek term ‘ekklesia‘, initially described civic assemblies but evolved to signify the gathering of believers in the New Covenant. It reflects a collective identity anchored in faith rather than a physical location.

Rooted in Israelite assemblies, which foundationally linked to worship at the Temple, the term in the New Covenant denotes the Body of Christ—a unified yet diverse community bound through shared doctrine, worship, and spiritual kinship. Paul’s letters further expound on this communal identity, emphasizing unity and the role of spiritual gifts.

Exploring these facets reveals deeper theological nuances.

Biblical Meaning of Church: Community, Worship, and Spiritual Body

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Definition | In the Bible, the church is not just a building but a community of believers who gather to worship, grow in faith, and carry out God’s mission. |

| Biblical Context | The term “church” originates from the Greek word “ekklesia,” meaning an assembly or gathering of called-out ones, representing the people of God. |

| Key Verses | – Matthew 18:20: “For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them.” – Ephesians 1:22-23: “And God placed all things under his feet and appointed him to be head over everything for the church, which is his body.” – Acts 2:42: “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer.” |

| Spiritual Significance | The church is described as the Body of Christ, where believers are united in faith and serve as His hands and feet to fulfill His purpose on Earth. |

| Practical Application | – Worship: A place to glorify God through prayer, song, and study of His word. – Fellowship: Building community and supporting one another. – Mission Work: Carrying the message of salvation to the world. |

| Symbolism | The church symbolizes unity in Christ, spiritual growth, and the hope of eternal life through salvation. |

| Role in Faith | The church nurtures spiritual maturity, provides accountability, and equips believers to live out their faith in daily life. |

Etymology of ‘Church’

The term ‘church‘ is etymologically derived from the Greek word ‘ekklesia,’ which historically referred to a gathering or assembly of citizens in ancient Greek city-states. In its original context, ‘ekklesia’ signified a civic assembly summoned for deliberation.

Over time, the term was adopted into Christian vernacular to describe the communal gathering of believers. This shift from a civic to a religious connotation underscores a significant transformation in the concept’s application.

Additionally, the theological import of ‘ekklesia’ in Christianity reflects a collective identity rooted in faith rather than geography. This nuanced evolution highlights how early Christians appropriated existing linguistic frameworks to articulate their emerging communal and spiritual realities, thereby embedding ‘church’ with layered meanings that extend beyond mere assembly.

Ecclesia in the New Testament

In the New Covenant, ‘ekklesia’ is used extensively to denote the assembly of believers, reflecting both a continuation of its original meaning and an expansion to encompass the theological concept of the Christian community.

Originally a secular term for a gathering or assembly, ‘ekklesia’ in the New Scripture context signifies the body of Christ, a unified collective of individuals bound by faith in Jesus.

This transformation underscores the shift from a general assembly to a sacred congregation.

Throughout the New Scripture, ‘ekklesia’ captures the essence of communal worship, doctrinal teaching, and mutual edification, thereby emphasizing the intrinsic unity and spiritual purpose of early Christian gatherings.

This nuanced usage of ‘ekklesia’ illustrates its pivotal role in defining the identity of the nascent Church.

Old Testament Roots

The concept of the church in the Old Covenant is closely linked to the assembly of Israelites, as seen in gatherings such as those at Mount Sinai, where the community was called together to receive God’s law.

Additionally, the significance of the Temple and Tabernacle underscores the early theological framework of a central place for communal worship and divine presence.

These elements collectively form the foundational understanding of a gathered people and sacred space that informs the New Covenant’s ecclesial identity.

Assembly of Israelites

Rooted in the Old Scripture, the term ‘assembly of Israelites‘ refers to the collective gathering of the Hebrew people, often for religious, judicial, or communal purposes, symbolizing their covenantal relationship with Yahweh.

This assembly, known as the ‘qahal‘ in Hebrew, is first seen in the context of the Sinai covenant where Moses convened the Israelites to receive the Law (Exodus 19-20).

Historically, it underscores the theocratic nature of Israelite society, where divine law governed communal life.

Theologically, these gatherings reinforced the identity of Israel as God’s chosen people, bound by His commandments.

Such assemblies were pivotal moments of communal solidarity, spiritual renewal, and covenant reaffirmation, reflecting the integral role of divine law in the life of Israel.

Temple and Tabernacle

Central to the religious life of ancient Israel, the concepts of the Temple and Tabernacle embody profound theological significance and historical development within the Old Scripture narrative. These structures served as physical manifestations of God’s presence among His people and were essential for worship practices.

The Tabernacle, a portable sanctuary, preceded the Temple and was used during Israel’s wilderness wanderings. The Temple, established later in Jerusalem, became the central place of worship.

Key theological and historical points include:

- Divine Dwelling: Both the Tabernacle and Temple symbolized God’s dwelling among His people.

- Covenant Relationship: These structures reinforced the covenantal relationship between God and Israel.

- Ritual Practices: They were focal points for sacrificial rites and festivals pivotal to Israelite worship.

Early Christian Usage

In early Christian literature, the term ‘church’ (Greek: ἐκκλησία, ekklēsia) was employed to describe both local congregations of believers and the universal community of Christians.

Historically, ‘ekklēsia’ was a secular term used in Greek city-states for assemblies of citizens. Early Christians adopted it to signify gatherings of the faithful, reflecting a sense of divine calling and communal identity.

Theologically, this term underscored the continuity of the Christian community with the Jewish qahal, or assembly, yet marked a distinct new covenant sealed by Christ.

The usage of ‘ekklēsia’ in the New Scriptures — such as in Acts and Pauline epistles — illustrates its dual application: addressing specific local groups (e.g., the church in Corinth) and the collective body of Christ’s followers.

Church as Community

The concept of ‘Church as Community‘ in the Bible encompasses foundational principles of fellowship, mutual spiritual growth, and collective worship.

Historically, the early Christian assemblies were characterized by their commitment to communal living and shared responsibilities, reflecting a theological emphasis on unity in the body of Christ.

This communal structure, rooted in scriptural teachings, facilitated not only spiritual development but also the practice of corporate worship, reinforcing the church’s role as a cohesive and nurturing entity.

Biblical Fellowship Principles

How does the concept of fellowship within the biblical context underscore the church as a community bound by spiritual kinship and mutual support?

Biblical fellowship principles highlight the church’s communal essence through several key aspects:

- Shared Belief: Early Christians gathered to uphold and disseminate shared doctrines, reinforcing their collective faith (Acts 2:42).

- Mutual Aid: The practice of sharing resources guaranteed that no member suffered need, exemplified by the pooling of possessions (Acts 4:32-35).

- Spiritual Kinship: Paul’s letters often emphasize the familial bonds among believers, calling them to bear one another’s burdens (Galatians 6:2).

These principles reveal the church as more than an institution; it is a living community united by divine love and service.

Spiritual Growth Together

Spiritual growth within the church community is fostered through collective engagement in worship, discipleship, and service, reflecting a holistic approach to nurturing faith.

Historically, the early church in Acts exemplified this communal growth, gathering in homes to break bread, pray, and study the apostles’ teachings (Acts 2:42-47). This model of fellowship not only strengthened their bonds but also attracted many to their cause, highlighting the transformative power of community. As believers supported one another, their actions reflected the core tenets of their faith, emphasizing love and unity. Understanding the meaning of the book of Acts requires recognizing how these early practices fostered a vibrant community that laid the foundation for the expansion of Christianity across the known world.

Theologically, the Apostle Paul emphasized the church as the Body of Christ, where every member contributes to the spiritual maturity of the whole (1 Corinthians 12:12-27).

This interconnectedness encourages believers to ‘spur one another on toward love and good deeds’ (Hebrews 10:24).

Consequently, the church as a community serves not merely as a gathering space but as a spiritual organism thriving through mutual edification and collective pursuit of Christlikeness.

Shared Worship Practices

As the church community grows spiritually through collective engagement, shared worship practices emerge as a fundamental expression of this unity and devotion.

Historically, these practices have been rooted in a rich tapestry of tradition and scripture. Theologically, they serve to bind the congregation, creating a shared sense of purpose and identity.

Key practices include:

- Communal Prayer: Reflects a collective reliance on divine guidance and intercession.

- Sacraments: Such as Communion, symbolize Christ’s sacrifice and foster spiritual intimacy.

- Scripture Reading: Promotes a unified understanding of God’s word, aligning the community’s values.

These practices not only enhance individual faith but also fortify the communal bonds, embodying the biblical notion of the church as the Body of Christ.

Symbolism in the Bible

Throughout the Bible, the concept of the ‘church’ is imbued with rich symbolism that reflects its multifaceted theological significance and historical evolution.

Symbolically, the church is often depicted as the ‘Body of Christ‘ (1 Corinthians 12:27), emphasizing unity and interdependence among believers.

Another potent symbol is the ‘Bride of Christ‘ (Ephesians 5:25-27), underscoring purity, love, and the covenantal relationship between Christ and the church.

Additionally, the ‘Temple of the Holy Spirit‘ (1 Corinthians 3:16) signifies the indwelling presence of God among His people.

These symbols collectively enhance our understanding of the church’s role not just as a congregation but as a dynamic, living entity integral to God’s redemptive plan throughout history.

Church in Paul’s Letters

Paul’s epistles provide a profound theological exploration of the church, intricately detailing its nature, purpose, and function within the early Christian communities. He emphasizes the church as the ‘Body of Christ,’ highlighting the spiritual unity and diversity of its members.

Key themes in Paul’s letters include:

- Unity in Christ: Paul stresses that all believers, regardless of background, form one body in Christ (1 Corinthians 12:12-27).

- Spiritual Gifts: He underscores the importance of diverse spiritual gifts, each contributing to the church’s edification (Ephesians 4:11-13).

- Mission and Outreach: Paul’s vision for the church includes evangelistic efforts and societal transformation (Romans 12:1-2).

These elements underscore the theological and communal dimensions Paul attributed to the early church.

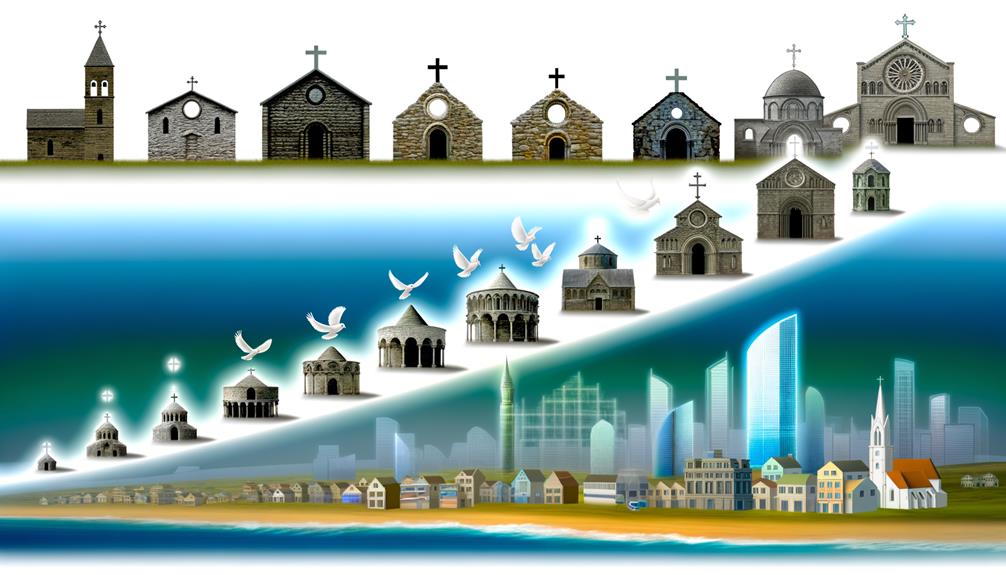

Evolution in Church History

The church’s evolution through history reflects a complex interplay of theological developments, sociopolitical influences, and cultural shifts that have continually reshaped its structure and practices. Initially, early Christian communities were informal, often meeting in homes. The Edict of Milan (313 AD) marked a significant shift, leading to the establishment of formal church buildings and hierarchical structures.

The Middle Ages saw the church become a dominant sociopolitical force, culminating in the Great Schism (1054 AD) which split Christianity into Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic branches. The Reformation (16th century) further diversified Christian practice, spawning Protestantism.

| Era | Key Development |

|---|---|

| Early Christianity | Informal gatherings in homes |

| Middle Ages | Dominance and the Great Schism |

| Reformation | Emergence of Protestantism |

This chronological progression underscores the church’s dynamic nature.

Modern Interpretations

As the church navigated through historical transformations, contemporary interpretations of its meaning in the Bible reflect an ongoing dialogue between traditional doctrines and modern theological perspectives.

Modern scholars often emphasize the dynamic and communal aspects of the church, viewing it not merely as a physical structure but as a living, spiritual entity.

This shift can be categorized into three primary interpretations:

- Ecclesial Community: Emphasizes the church as a gathering of believers, focusing on community and fellowship.

- Missional Church: Highlights the church’s role in societal transformation and outreach.

- Inclusive Church: Advocates for a diverse and welcoming community, reflecting global and cultural inclusivity.

These perspectives illustrate a multifaceted understanding that continues to evolve alongside societal changes.

Conclusion

Throughout history, the concept of ‘church‘ has evolved from the Greek ‘ecclesia’ to signify a community of believers rather than just a physical structure.

In Paul’s letters, ‘church’ denotes both local gatherings and the universal body of Christ.

A metaphor for this can be seen in a tree: its roots (Old Scripture) anchor it, while its branches (New Scripture and beyond) reach out, symbolizing growth and unity.

This dynamic understanding underscores the church’s enduring theological and communal significance.