Meaning of the Word Slave in the Bible: Bondage

The word ‘slave‘ in the Bible, derived from terms such as the Hebrew ‘eved’ and Greek ‘doulos,’ refers to a range of servile conditions from bonded laborers to chattel slaves. These definitions reflect the complex socio-economic structures of ancient Israel and the Greco-Roman world.

Biblical texts regulate servitude with nuanced ethical and legal codes, mandating humane treatment and periodic release. The theological implications highlight divine principles of justice and dignity within societal norms.

A deeper study into these terminologies reveals the multifaceted nature of slavery as depicted in the Scriptures and its evolving interpretations.

Meaning of Slave in the Bible: Historical Context and Spiritual Implications

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | In the Bible, “slave” refers to individuals in servitude, either due to debt, conquest, or social status. It is also used metaphorically for servanthood to God. |

| Biblical Context | Slavery was a common practice in ancient times, differing significantly from modern understandings, often regulated by laws in the Old Testament (Exodus 21:2-11, Leviticus 25:39-55). |

| Key Verses | Galatians 3:28 (all are one in Christ Jesus), Romans 6:22 (freedom from sin and slavery to righteousness), Philemon 1:16 (treating a slave as a brother in Christ). |

| Spiritual Symbolism | Symbolizes submission and servanthood to God, emphasizing the believer’s devotion and obedience to Him (Romans 6:16-18). |

| Cultural Implications | Biblical slavery often involved humane treatment, unlike the racialized and dehumanizing systems in more recent history. |

| Christ’s Teachings | Jesus redefined servanthood, teaching humility and service to others as an expression of love and faith (Mark 10:45, John 13:12-17). |

| Significance Today | Encourages a deeper understanding of freedom in Christ, highlighting themes of redemption, equality, and loving service. |

Hebrew Terms for Slave

The Hebrew Bible uses several terms to denote slaves, each carrying distinct connotations and reflecting various aspects of servitude within ancient Israelite society.

The primary term, ‘eved,’ encompasses a broad spectrum of servitude, ranging from bonded laborers to more permanent chattel slaves.

Another term, ‘amah,’ specifically refers to a female servant, often indicating a lower social status or a role within domestic settings.

‘Mishneh‘ denotes a higher-ranking servant, sometimes akin to a steward or overseer.

These nuanced terms highlight the complexity of social hierarchies and the diverse experiences of servitude in ancient Israel.

The theological implications of these terms also underscore the ethical and moral considerations embedded within the biblical legal codes and societal norms.

Greek Terms for Slave

The Greek terms for slave found within biblical texts encompass a range of meanings, reflecting various social and legal conditions.

The term ‘doulos‘ often translates to either bondservant or slave, raising questions about voluntary servitude versus coerced labor.

Additionally, ‘pais‘ can denote either a servant or a child, while ‘andrapodon‘ specifically refers to individuals captured in war, thereby highlighting the multifaceted nature of servitude in the ancient world.

Doulos: Bondservant or Slave?

Among the Greek terms for ‘slave,’ the word ‘doulos‘ holds significant theological and historical implications in biblical texts. Historically, ‘doulos’ referred to a person bound in servitude, often devoid of personal freedom.

Theologically, the New Covenant employs ‘doulos’ to illustrate a profound spiritual servitude to Christ, suggesting a voluntary, devoted relationship rather than mere coercion.

Key passages, such as Romans 1:1, where Paul identifies himself as a ‘doulos’ of Christ, underscore a sense of willing commitment and service.

This duality of meaning—both as an actual slave and a devoted bondservant—invites reflection on the nature of spiritual allegiance, contrasting earthly bondage with divine servitude that promises ultimate liberation through faith.

Pais: Servant or Child?

Exploring the term ‘pais‘ in biblical Greek reveals its dual connotations as both ‘servant’ and ‘child,’ necessitating a nuanced interpretation within scriptural contexts.

Historically, ‘pais’ could denote a young servant, often a minor, highlighting a social structure where age and status intersected.

Theologically, its application varies, sometimes referring to a servant in a household, as seen in Matthew 8:6, and at other times to a child, as in Luke 2:43.

This duality underscores the complexity of translating ancient texts and understanding their socio-cultural backdrop.

Contextual analysis is essential to discern whether ‘pais’ emphasizes service or familial relationship, thereby enriching our comprehension of biblical narratives and their intended meanings.

Andrapodon: Captured in War

Moving from the dual connotations of ‘pais,’ we encounter the term ‘andrapodon,’ which explicitly refers to individuals captured in war and subsequently enslaved in ancient Greek contexts.

The theological and historical implications of andrapodon provide a stark contrast to other forms of servitude mentioned in biblical texts. This term encapsulates:

- The brutal reality of war and its impact on human lives.

- The commodification of war captives as property.

- The social and economic structures that perpetuated slavery.

- The moral and ethical considerations in ancient societies.

Understanding ‘andrapodon’ is vital for comprehending the multifaceted nature of slavery in historical and theological contexts, providing deeper insight into the lived experiences of those enslaved.

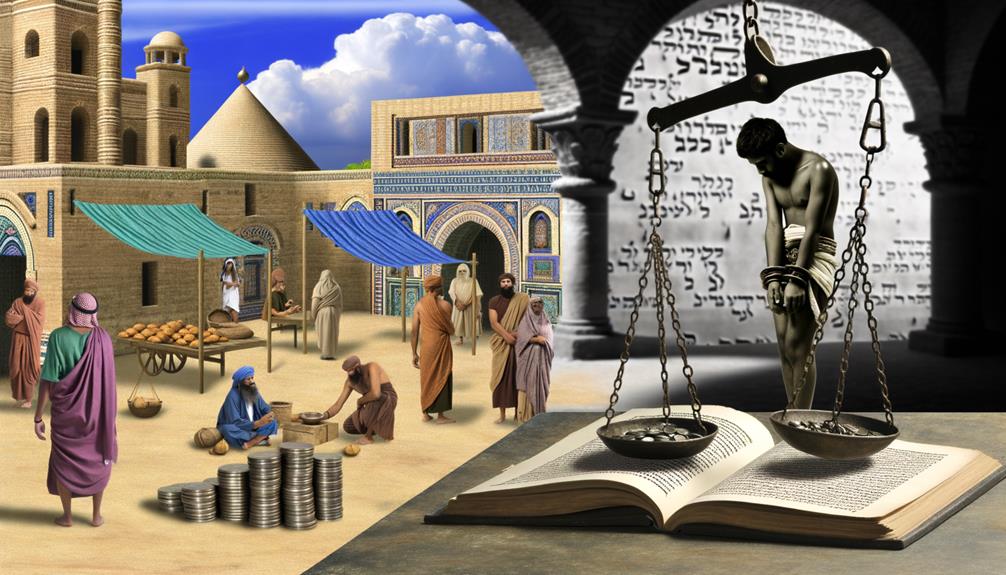

Historical Context

Understanding the historical context of the term ‘slave’ in the Bible necessitates examining the socio-economic and cultural conditions of ancient Near Eastern societies. In these civilizations, slavery was an entrenched institution, influenced by conquests, debts, and social stratification.

The biblical texts emerged from a milieu where slavery was not just an economic reality but also a legal and social framework. Hebrew laws, such as those in Exodus and Deuteronomy, reveal a complex system regulating the treatment, rights, and obligations of slaves.

This historical backdrop is essential for comprehending how biblical authors and audiences perceived and utilized the term. Consequently, the term ‘slave’ in the biblical context is deeply intertwined with the era’s prevailing norms and economic structures. Furthermore, the concept of slavery in biblical texts reflects not only social hierarchies but also the theological implications surrounding authority and power. Understanding these dynamics sheds light on the meaning of dominion in the Bible, as it often refers to a divinely sanctioned order that justifies various forms of servitude and governance. Thus, the interpretations of these terms are essential for grasping the complexities of moral, ethical, and spiritual discussions present in scriptural passages.

Cultural Norms

Understanding the cultural norms of ancient societies is vital to comprehending the biblical use of the term ‘slave.’

Examining the societal structures and practices within the biblical context reveals a complex interplay of economic, social, and religious factors.

Additionally, comparing these norms with those of contemporary cultures offers significant insights into the varying perceptions and treatments of slavery.

Ancient Societal Structures

The concept of slavery in the Bible must be understood within the context of ancient societal structures, where cultural norms greatly differed from contemporary perspectives on human rights and freedom.

Societal frameworks of the ancient Near East, including those depicted in biblical texts, were complex and multifaceted. Key aspects include:

- Economic Systems: Slavery was often tied to economic survival and debt repayment.

- Social Hierarchies: Rigid class distinctions influenced the roles and treatment of slaves.

- Legal Codes: Laws governing slavery varied, reflecting both protective and exploitative measures.

- Household Dynamics: Slaves were integral to household functions, often living with their masters’ families.

Understanding these elements aids in grasping the ancient biblical context of slavery.

Biblical Contexts and Practices

Biblical contexts and practices surrounding slavery were deeply intertwined with the cultural norms of the ancient Near East, reflecting a society where such institutions were both legally sanctioned and socially embedded.

In the Old Scripture, laws found in Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy regulated the treatment of slaves, often distinguishing between Hebrew and foreign slaves. Theological implications of these practices were complex; servitude could be both punitive and economic, yet also included provisions for protection and eventual release, particularly for fellow Israelites.

The New Scripture’s treatment of slavery, seen in Paul’s epistles, often instructed ethical behavior within the existing societal framework rather than calling for institutional abolition, reflecting the embeddedness of slavery in the cultural and economic fabric of the time.

Comparative Cultural Views

Comparative analysis of cultural norms reveals that the practice and perception of slavery in biblical times were not unique to ancient Israel but were part of a broader Near Eastern context where servitude was a pervasive social and economic institution.

Various cultures, including:

- Mesopotamia: Codified slavery laws in the Code of Hammurabi.

- Egypt: Utilized slave labor for monumental construction.

- Assyria: Enslaved captives from military conquests.

- Persia: Integrated slaves into household and agricultural roles.

These societies shared commonalities in the institutionalization of slavery, yet each had unique legal, economic, and social frameworks that governed the lives of slaves.

Understanding these comparative cultural views aids in grasping the theological implications within the biblical narrative.

Types of Servitude

Exploring the different forms of servitude in the Bible reveals a complex interplay of social, economic, and theological dimensions.

Biblical texts distinguish between various types of servitude, including debt servitude, where individuals worked to repay financial obligations, and chattel slavery, where individuals were considered property.

Hebrew servitude, often limited to six years, contrasts with the perpetual servitude of foreign slaves.

Theological aspects further complicate these distinctions; divine laws mandated humane treatment and periodic release, reflecting a covenantal ethos.

The Year of Jubilee, for example, emphasized liberation and restoration.

Understanding these types of servitude requires a nuanced appreciation of the historical context and theological principles underpinning biblical injunctions, which aimed to balance social order with moral imperatives.

Economic Implications

The diverse forms of servitude outlined in biblical texts also carried significant economic implications that shaped ancient Israelite society. The economy depended on various labor structures, which included:

- Debt Servitude: Individuals sold themselves to repay debts, impacting social mobility.

- Household Slaves: Integral to the functioning of wealthy households, these slaves contributed to domestic and economic stability.

- Agricultural Labor: Slaves worked on farms, ensuring food production and land management.

- Skilled Labor: Some slaves held specialized skills, influencing trade and craftsmanship.

These categories highlight the multifaceted role of servitude in sustaining the economic framework of ancient Israel, reflecting both dependency and productivity within the community.

Legal Aspects

Legal provisions regarding slavery in the Bible reflect a complex interplay of moral, social, and religious norms that governed the institution of servitude in ancient Israel.

Biblical laws, such as those found in Exodus 21, Leviticus 25, and Deuteronomy 15, regulated the treatment, rights, and obligations of slaves and their masters.

These texts established limits on the duration of servitude, typically mandating the release of Hebrew slaves after six years, while foreign slaves could be held indefinitely.

Additionally, laws provided protections against harsh treatment, emphasizing the humane aspect of servitude.

The Jubilee year, occurring every fifty years, also mandated the freeing of slaves, signifying a socio-religious reset.

Consequently, biblical legal frameworks sought to balance economic realities with ethical considerations.

Moral Perspectives

Moral perspectives on slavery in the Bible reveal a complex interplay between ethical imperatives and the socio-cultural context of ancient Israel. Biblical texts often appear to condone slavery, yet they also impose moral restrictions, reflecting a nuanced ethical landscape.

Key points include:

- The Hebrew Bible mandates humane treatment of slaves, including rest on the Sabbath (Exodus 20:10).

- Hebrew slaves were to be released after six years of service (Exodus 21:2).

- The New Covenant calls for mutual respect between slaves and masters (Ephesians 6:5-9).

- Prophetic literature often condemns oppression and advocates for justice (Isaiah 58:6).

This intricate moral framework highlights the tension between divine ideals and human practices.

Modern Interpretations

Modern interpretations of the word ‘slave‘ in the Bible often grapple with reconciling ancient texts with contemporary ethical standards and historical understandings.

The Hebrew term ‘ebed’ and the Greek ‘doulos’ encompass a range of servitudes, from indentured servitude to chattel slavery.

Theological analysis seeks to understand these terms within the socio-economic context of ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman cultures, where slavery was an embedded institution.

Scholars argue that biblical texts reflect differing attitudes toward slavery, sometimes depicting it as a social norm while at other times advocating for humane treatment and eventual liberation.

Modern exegesis therefore attempts to balance historical context with a commitment to human dignity, urging a nuanced reading that neither anachronizes nor absolves ancient practices.

Conclusion

The term ‘slave‘ in the Bible encompasses various Hebrew and Greek terms, each with nuanced meanings shaped by historical, cultural, and economic contexts.

Significantly, approximately 10% of the population in ancient Israel might have been in some form of servitude.

Legal aspects often provided certain protections, while moral perspectives varied.

Modern interpretations continue to grapple with these complexities, emphasizing the importance of understanding the original contexts to fully appreciate the biblical texts’ multifaceted dimensions.