None of These Words Are in the Bible Meaning: Explain

Many commonly quoted phrases, such as ‘cleanliness is next to godliness‘ and ‘God helps those who help themselves,’ are often misattributed to the Bible but do not appear in its texts. These expressions reflect broader cultural values and ethical teachings rather than scriptural origins.

The idea that ‘money is the root of all evil’ is a misinterpretation; the Bible actually states ‘the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil’ which shifts the focus to human desires. Understanding these distinctions uncovers the rich interplay between sacred texts and societal values, revealing deeper insights into how religious teachings shape everyday moral concepts.

Words Commonly Misattributed to the Bible: Meaning and Biblical Relevance

| Word/Phrase | Meaning/Explanation | Biblical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Trinity | Refers to the unity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in Christian doctrine | The concept is supported by verses like Matthew 28:19, but the term itself is not used in the Bible |

| Rapture | A belief in the end-times event where believers are taken to heaven | Derived from 1 Thessalonians 4:17, but the word rapture does not appear in the text |

| Free Will | The ability of humans to choose between good and evil | Implied through verses like Deuteronomy 30:19 and Joshua 24:15, but not directly named |

| Bible | The sacred scriptures of Christianity | The term Bible comes from the Greek biblia, meaning books, and is not explicitly used in Scripture |

| Sunday Worship | The practice of worship on the first day of the week | Early Christians began worshiping on Sunday in honor of Christ’s resurrection, referenced in Acts 20:7 |

| Good Samaritan | A person who helps others selflessly | This phrase originates from Jesus’ parable in Luke 10:25-37, but the term is a later creation |

| Original Sin | The concept of humanity inheriting sin from Adam and Eve | The idea is based on Romans 5:12-19, though the exact phrase is not found in the Bible |

| Hell | A place of eternal punishment for sinners | The Bible uses terms like Gehenna, Hades, and Sheol, but Hell is an English interpretation |

Cleanliness Is Next to Godliness

The phrase ‘Cleanliness is next to godliness,’ though not found explicitly in the Bible, underscores a historical and theological emphasis on the importance of physical and spiritual purity within Judeo-Christian teachings.

This axiom reflects ancient Jewish practices of ritual purification, such as those detailed in Leviticus, where cleanliness was a prerequisite for worship.

In addition, New Covenant writings also echo this sentiment by emphasizing inner moral purity. For instance, Jesus’ teachings in the Gospels highlight the significance of purifying one’s heart and intentions.

The broader theological context suggests that maintaining cleanliness is not merely about physical hygiene but also about embodying a state of holiness and readiness to engage in a relationship with the Divine.

God Helps Those Who Help Themselves

While the concept of cleanliness underscores the importance of purity, the adage ‘God helps those who help themselves’ introduces a complementary perspective on personal responsibility and divine assistance. Despite its popularity, this phrase does not originate from the Bible. Instead, it emphasizes human initiative and effort, suggesting that divine aid aligns with individual endeavor.

To contextualize:

| Phrase | Origin | Biblical Reference |

|---|---|---|

| God helps those who help themselves | Ancient Greek, popularized by Benjamin Franklin | Absent |

| Cleanliness is next to godliness | John Wesley’s sermon, 1778 | Absent |

| Spare the rod, spoil the child | Proverb from Samuel Butler | Proverbs 13:24 |

Thus, the phrase underscores an alignment of human diligence with divine support, reflecting a broader ethical stance.

Spare the Rod, Spoil the Child

Examining the phrase ‘Spare the rod, spoil the child’ necessitates an exploration of its origins, interpretations, and implications within both historical and contemporary contexts.

Although commonly attributed to biblical scripture, the exact phrase does not appear in the Bible. Its roots trace back to a 17th-century poem by Samuel Butler, which reflects broader cultural attitudes towards child-rearing.

Biblically, verses such as Proverbs 13:24 (‘Whoever spares the rod hates their children, but the one who loves their children is careful to discipline them’) inform the sentiment.

Historically, interpretations have varied, influencing disciplinary practices. In modern times, the phrase is often debated, with some advocating for non-physical forms of discipline in light of psychological research on child development.

Money Is the Root of All Evil

The phrase ‘Money is the root of all evil’ is often cited but frequently misunderstood and misquoted.

A closer examination reveals that the actual biblical quote from 1 Timothy 6:10 states, ‘For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil,’ highlighting the distinction between money itself and the human emotions attached to it.

This misinterpretation has significant implications for theological teachings and societal attitudes towards wealth and morality.

Context of the Phrase

Understanding the context of the phrase ‘Money is the root of all evil’ necessitates a careful examination of its biblical origin and the broader narrative in which it is situated. The phrase is derived from 1 Timothy 6:10, which actually states, ‘For the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil.’

This subtle but critical difference shifts the focus from money itself to the attitude towards it. The broader narrative addresses the moral and ethical challenges associated with wealth and the human propensity for greed.

| Biblical Text | Actual Phrase | Contextual Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Source | 1 Timothy 6:10 | New Scripture epistle |

| Actual Wording | ‘For the love of money…’ | Emphasis on human desire |

| Broader Narrative | Ethical warnings about wealth | Guidance on moral conduct |

| Interpretational Focus | Attitude towards wealth | Impact of greed on spiritual well-being |

Misinterpretation and Impact

Misinterpretations of the phrase ‘Money is the root of all evil’ have led to profound misconceptions about wealth and morality within both religious and secular contexts.

Such distortions can result in:

- Economic Misjudgment: Viewing wealth inherently as immoral can discourage financial prudence and investment.

- Moral Polarization: Equating affluence with vice may foster undue guilt among the prosperous and resentment among the less fortunate.

- Philanthropic Hesitancy: Misunderstanding the role of wealth can impede charitable initiatives, as potential donors may fear moral compromise.

- Societal Division: Misinterpretations can exacerbate class conflicts, undermining social cohesion and promoting economic disparity.

Addressing these misinterpretations requires a nuanced understanding of the phrase’s true implications, fostering balanced perspectives on wealth and ethics.

Actual Biblical Quote

Clarifying the actual biblical quote, ‘For the love of money is the root of all evil,’ shifts the focus from wealth itself to the underlying attitude towards it, offering a more precise ethical framework.

This distinction, found in 1 Timothy 6:10, underscores that money per se is not inherently evil; rather, it is the excessive desire for it that leads to moral corruption.

This interpretation aligns with broader biblical teachings that prioritize virtues such as contentment and generosity over materialism.

Understanding this quote in its proper context calls for a nuanced analysis of human motivations and the ethical use of resources, thereby promoting a balanced view that discourages greed while acknowledging the practical role of money in society.

The Seven Deadly Sins

The concept of the Seven Deadly Sins traces its origins to early Christian teachings and has evolved considerably throughout history.

Examining their historical context reveals the theological and moral frameworks that shaped their prominence, while modern interpretations highlight their continuing relevance in contemporary ethical discourse.

This discussion aims to dissect these points, providing a thorough understanding of their enduring impact.

Origins and Historical Context

Tracing the origins of the Seven Deadly Sins reveals their deep roots in early Christian teachings and the writings of influential theologians such as Evagrius Ponticus and Gregory the Great. Evagrius, a 4th-century monk, initially proposed eight evil thoughts, which later became codified by Pope Gregory I in the 6th century into the seven sins known today: pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony, and sloth.

The historical context includes:

- Evagrius Ponticus’ Eight Logismoi: Early conceptual framework.

- Gregory the Great: Formalized the list in his ‘Moralia in Job’.

- Monastic Tradition: Emphasized these sins in spiritual training.

- Medieval Scholasticism: Further refined their theological implications.

Understanding these origins provides essential insight into their enduring significance in Christian moral theology.

Modern Interpretations and Relevance

In contemporary Christian thought, the Seven Deadly Sins are frequently reexamined to address the evolving moral and ethical challenges of modern society. This reconsideration often highlights how these ancient concepts can be applied to contemporary issues such as consumerism, digital addiction, and social justice. Scholars argue that these sins still provide a valuable framework for understanding human behavior and morality.

| Sin | Traditional Context | Modern Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Pride | Excessive self-love | Narcissism, social media vanity |

| Greed | Desire for material wealth | Consumerism, corporate corruption |

| Envy | Resentment of others | Social media envy, competition |

Such reinterpretations underscore the enduring relevance of these moral teachings, adapted to the complexities of today’s world.

The Apple in the Garden of Eden

While commonly depicted as an apple, the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden is not explicitly identified in the biblical text, leading to various interpretations and symbolisms throughout history. The original Hebrew term used in Genesis is ‘peri,’ a generic word for fruit. This ambiguity has given rise to different scholarly theories:

- Pomegranate: Some suggest it symbolizes fertility and knowledge in ancient cultures.

- Fig: Due to the immediate reference to fig leaves for clothing, this fruit is another candidate.

- Grape: Linked to early Jewish traditions and symbolizing wine and temptation.

- Quince: Renowned in ancient texts for its association with love and beauty.

These interpretations highlight the complexities and evolving understandings of biblical texts, providing rich grounds for theological and literary exploration. The underlying themes and messages often reflect the cultural and historical contexts in which they were developed, challenging readers to reconsider their implications for contemporary life. Furthermore, the word Bible etymology explained reveals its roots in the Greek term “biblia,” meaning “books,” which underscores the diverse nature of its content and the multitude of voices that contribute to its narratives. As we delve deeper into these texts, we uncover not only their sacred significance but also their literary richness and enduring relevance across generations.

Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust

The phrase ‘ashes to ashes, dust to dust’ originates from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer and encapsulates the biblical concept of human mortality and the transient nature of life. This articulation, although not verbatim in the Bible, reflects scriptural themes found in Genesis 3:19 and Ecclesiastes 3:20, emphasizing the ephemeral existence of humans and their inevitable return to the earth.

| Biblical Reference | Conceptual Parallel |

|---|---|

| Genesis 3:19 | “For dust you are and to dust you will return.” |

| Ecclesiastes 3:20 | “All go to the same place; all come from dust, and to dust all return.” |

| Job 34:15 | “All flesh would perish together, and man would return to dust.” |

| Psalm 103:14 | “For he knows our frame; he remembers that we are dust.” |

| 1 Corinthians 15:47 | “The first man was of the dust of the earth.” |

This exploration reveals the theological and existential dimensions of human life as understood within Christianity.

The Three Wise Men

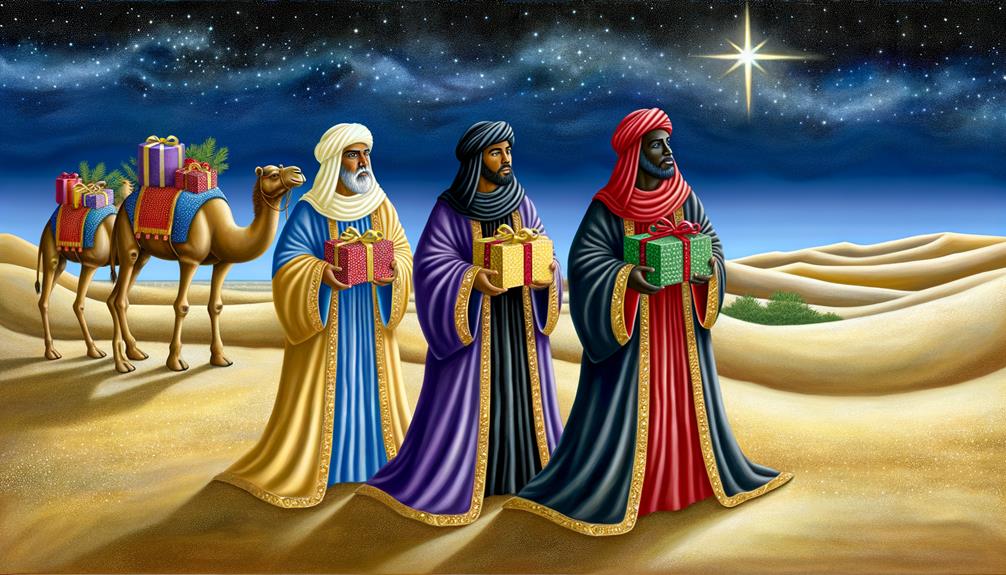

Magi from the East, commonly referred to as the Three Wise Men, play a pivotal role in the Nativity narrative by symbolizing the recognition of Jesus’ divine kingship beyond the Jewish world. Their journey, as recounted in the Gospel of Matthew, is rich with theological significance.

Scholars often analyze their visit through four primary lenses:

- Historical Context: Examining the geopolitical and cultural backdrop of the Magi’s journey.

- Symbolism: Understanding the gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh as symbols of Jesus’ kingship, divinity, and eventual suffering.

- Prophetic Fulfillment: Investigating how their visit fulfills Old scriptures prophecies.

- Inclusivity: Reflecting on the inclusion of Gentiles in the acknowledgment of Jesus’ messianic role.

These elements collectively underscore the global and inclusive nature of Christ’s mission.

To Thine Own Self Be True

In contemplating the broader implications of the Magi’s journey and their recognition of Jesus, one is reminded of the timeless importance of personal integrity and authenticity, encapsulated in the adage, ‘To thine own self be true.’

Although this phrase originates from Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet,’ it resonates with biblical themes of self-awareness and moral steadfastness. The Magi’s unwavering commitment to their quest, guided by their inner convictions, exemplifies this principle.

Their journey symbolizes the pursuit of truth and the courage to follow one’s path despite external pressures. In a broader theological context, this adage aligns with scriptural exhortations to live in accordance with one’s divinely inspired purpose, reinforcing the essentiality of aligning one’s actions with inner truth.

Conclusion

The aforementioned phrases, often misattributed to biblical scripture, serve as allegorical signposts within societal moral landscapes.

Each aphorism, while absent from canonical texts, illustrates the collective ethos and cultural interpretations shaped over centuries.

These maxims, rooted in tradition rather than divine origin, reflect humanity’s endeavor to encapsulate complex theological and ethical principles into accessible wisdom.

Recognizing their extrabiblical origins promotes a nuanced understanding of how religious and moral guidance evolves beyond its sacred texts.